I've been thinking about this for several months now, about what to do with this word, "heritability."

The problem is that it is often used in reference to genetics, but it can either mean "something caused by genetics" or "something not caused by genetics."

Today, researchers rely on genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to find the genetic variants that are relevant to a specific trait. In GWAS the genomes of individuals are analyzed to see if particular genetic variants are correlated with variation in traits of interest. GWAS results have identified hundreds of variants underlying phenotypic variation in humans, mice, fruit flies, rice, maize, and many other taxa. Yet, despite the large number of alleles that have been identified using this technique, the amount of phenotypic variation they explain is just a fraction of what twin and pedigree studies predict is heritable. For example, twin studies have shown that approximately 80% of variation in human height can be explained by genetic factors (Silventoinen et al., 2012). However, the results of the best powered GWAS only explain around 20% of such variation (Wood et al., 2014). This gap is known as the ‘missing heritability problem’.

The "missing heritability problem" is pretty clearly a problem with predictions about genetics - far less evidence has been found, than was anticipated, for specific genes influencing specific human traits.

And yet, for example, educational attainment is also said to be an "heritable" trait :

SNP heritability increased with socioeconomic deprivation for fluid intelligence, educational attainment, and years of education. Polygenic scores were also found to interact with socioeconomic deprivation, where the effects of the scores increased with increasing deprivation for all traits.

"Years of education" is a social phenomenon, not a genetic one. But it is still called "hereditable."

To give one extreme example: in American chattel slavery, not only were slaves rarely taught to read, they were often actively prevented from learning to read. So illiteracy could be said to be highly "heritable" in American slaves - the children of slaves were about as likely to be illiterate as their parents. But obviously this has nothing to do with a genetic ability to learn how to read.

The way heritable is used, it sounds like it describes an action - as if "heritable" educational attainment is the act of passing down educational attainment from one generation to the next.

Instead "heritable" is the observation that nothing has changed from one generation to the next. "Heritable" is nothing more than a statistical description of stasis.

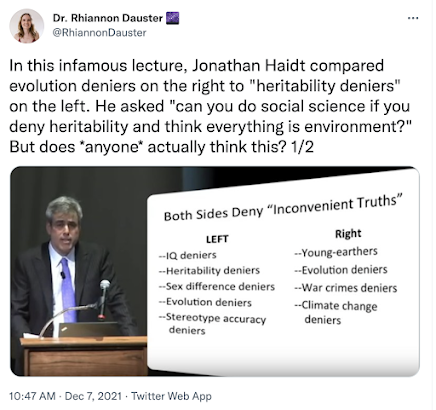

Apparently Steven Pinker and Jonathan Haidt (a Koch money beneficiary via Heterodox Academy) both believe the term "heritability" means "genetic."

But hereditarians would want to believe "heritability" means "genetic" because their answer to everything is "genes."

I have long joked that the "nature assumption" is so strong among promoters of sociobiology that this is how they do their studies:

Step one: observe a human behavior

Step two: declare the cause "genetics"

Step three: write a paper declaring the victory of nature over nurture

The term "nature assumption" is a nod to that darling of biosocial criminology, Judith Rich Harris, who wrote "The Nuture Assumption" and who, I recently discovered, was hugely influenced by Steven Pinker, which I will discuss in a future post.

Recently hereditarians were taking yet another premature victory lap for nature over nurture, this time based on claims by "behavioral geneticist" Kathryn Paige Harden. Those claims were immediately assumed to be a victory for race pseudoscience by people like Quillette author Nathan Cofnas:

Here's how Lewis-Kraus described Harden's own account of the tool she uses to address the most loaded social questions of our time:GWAS simply provides a picture of how genes are correlated with success, or mental health, or criminality, for particular populations in a particular society at a particular time.....GWAS results are not "portable"; a study conducted on white Britons tells you little about people in Estonia or Nigeria.That is, the genome makes people unequal, but it does so by an unclear mechanism, the effects of which are contingent on a person's social position in a particular time and place. Yet the reader was supposed to share Harden's regret or bafflement that Darity, a scholar of the material processes of racial inequality, would be hostile to her work.

In other words, Harden absolutely does not have evidence for the claim that correlations between some social conditions and some GWAS results are caused by genes, but nevertheless she goes ahead and makes that claim.

And not only makes the claim - she compares those who have doubts about her claim with bank robbers. But being a drama queen seems to be a pretty common trait, over the years, among promoters of sociobiology and its many sub-categories: evolutionary psychology, behavioral genetics, race science, etc. Is "drama queen" an heritable trait for sociobiologists?